The Father of the unguarded moment

- Jun 13, 2020

- 4 min read

By Harry Stocker

I can promise to be candid, not, however, to be impartial – Johann Wolfgang Goethe

Erich Salomon was born to a German, Jewish family in Berlin, 1886. Details of his early life are sparse, but he studied voraciously in zoology, engineering and finally graduated with a doctorate in law in 1913.

After completing his education, he was drafted in the German army. He was part of the decisive defeat at the Miracle of the Marne and spent the rest of the war in a PoW camp, where he learnt French.

Just like his academic pursuits, his early career was varied. He spent time at the Berlin stock exchange, a piano factory and even founded his own car rental agency. Finally, in 1925, he joined Ullstein publishing house. It was there two years later, at the age of 41, he first picked up a camera. The beginnings of his career in photography are comically mundane, taking photographs to be used in a legal proceeding for Ullstein. But something, and it wasn’t just a shutter, seemed to click for Salomon. His obsession was ignited.

Wiki Commons

Bold and connected, he became determined to photograph the courtroom, and began to smuggle in cameras. Photography was strictly forbidden, so any photos would serve as a stunning exclusive. To take a photo, he cut a hole in his bowler hat, allowing his lens to poke through and he simply held it level to his chest. Another occasion saw him smuggle a briefcase into court, rigged with an intricate lever system to cue the shutter. Other notable incidents include being the first photographer to capture the Supreme Court, with a camera concealed in a sling. And in an another, setting up an extra music stand, taking his place among an orchestra, coat and tails and all, with his ‘bagpipes’ at the ready. This was the birth of candid photography.

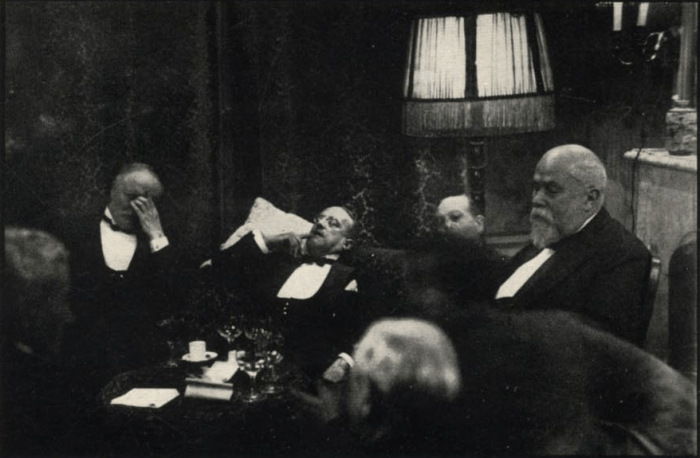

He was a small man, and like an apparition, managed to dance between the visible and invisible. He was persistent, quiet and confident. After his sensational courtroom portraits received national acclaim, he began to work as a full-time freelance photographer. In 1928 he started to document political summits and conferences of the League of Nations. In August, at the Pact of Paris, an international agreement to essentially outlaw war, Salomon strolled in and sat at the empty chair of the Polish delegate. But it wasn’t always this easy to gain access to these closed off meetings, and so a method was devised: Arrive late, dress immaculately, speak unintelligibly, “if they can’t understand you, they will assume you are supposed to be there.” His book, “Famous Contemporaries in Unguarded Moments” was published in 1931.

Quickly, Salomon shifted in the eyes of the politicians he surrounded himself with. From outsider, to uneasy constant and finally, to vital necessity. A common joke at the time was “What three things do you need for a League of Nations meeting? A few Foreign Secretaries, a table and Dr Erich Salomon.” Similarly, before many an important meeting, someone would grin and ask, “Where is Dr Salomon?”

But to reflect on this for just a moment, the sinister implications reveal themselves. What made Salomon’s work so groundbreakingly profound was their candour. His unique approach allowed individual moments to be memorialized in all their abrupt honesty. This effect was particularly pronounced when applied to the ministers and foreign dignitaries. Eroded was the elitist veneer that seeped through the stuffy portraits, tucked away in the grand palaces of the Low Countries. For the first time, the public saw them tired, angry, in shrieking, undignified laughter. For the first time, they were human.

Undoubtedly, they soon came to realise the benefits. The mere acknowledgment of Salomon’s omnipresence characterised the perversion of his intent. “Where is Dr Salomon?” they would cry. No longer a fly on the wall, or a man in the crowd surreptitiously angling his bowler hat. He had been welcomed into the establishment with open arms. Once he had lost his clandestine element, his work is interpreted fundamentally differently, illuminated in a new, meretricious and cynical light.

Photo courtesy of Bristol based photographer, Archie Benn

Previously, the viewer was compelled to feel a sense of immersion. They were hurled up close and personal, in media res, into an unseen and dangerous world. Where the decision made in exquisite, gilded halls had the potential to carve history from thin air. They were present, but unseen, Peeking behind the heavy stage curtain of the political apparatus. They had a man on the inside.

But with the political commodification of Salomon, they were expelled from the peepshow democracy, for a photographer can only capture what their subject choses to yield. And it is with bitter irony and tragedy that the question of, “Where is Dr Salomon?” is asked once again. In July 1944, the multilingual, war veteran, Doctor of Law, revolutionary photojournalist, husband and father was reduced to nothing else but a Jew, murdered by the Nazis, and died in Auschwitz with his wife and youngest son.

Comments