21st-century North-South divide: the bleak reality of child poverty

- Jun 1, 2020

- 4 min read

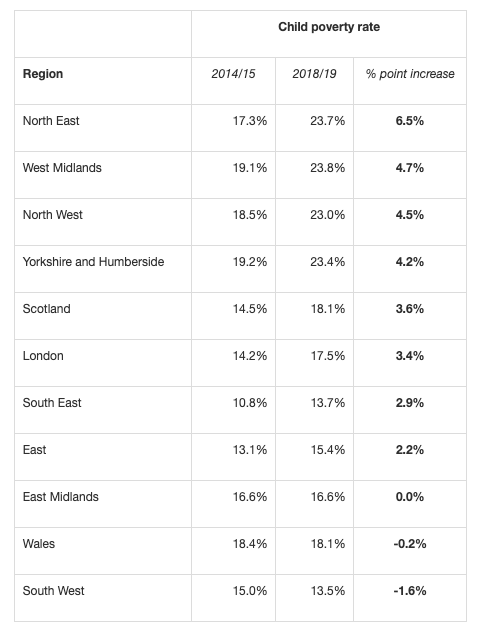

Last week, a study carried out by Loughborough University revealed the harrowing extent of child poverty in the UK and the great disparity that exists between the North and South of England. With the North East, North West and Yorkshire all experiencing an increase in child poverty cases at least two times greater than any Southern region, it highlights today’s omnipresent North-South economic divide .

In the last five years, the UK has experienced one of the highest increases in child poverty cases ever recorded, with an estimated 4.2 million children now living below the breadline.

The number of Northern children living in poverty has significantly increased in comparison to the South. Whereas Southern regions, including London, have experienced an average 1.57% increase, the North has seen a hike of 5.06%.

Increases in child poverty cases reveal that the North-South divide still exists

Although seemingly small percentages, this translates to nearly a third of all under-16s in the UK living below the median income: the equivalent of nine in every classroom.

Geographical poverty in the UK today

Loughborough’s findings show that out of the 20 constituencies experiencing the most significant increase in child poverty cases, 13 are situated in the North of England. In Middlesbrough, where the rise was most severe at 15.6%, almost one in five children now live under the poverty line.

It seems wrong to compare “where is worse-off” when questions of “who is worse-off” are ignored. Unfortunately, geographical poverty and its devastating effects are nothing new.

Since the 1980s, the economic gap between the North and South of England has only widened, after Conservative government policies designed to achieve nationwide economic revival instead increased regional divisions, thereby creating “politics of inequality”.

Recent austerity measures have meant this has further cemented itself in varying aspects of children’s lives. Today, more than half of the secondary schools in the North’s most deprived communities are judged to be less than “good” by Ofsted. This is compounded by countrywide cuts to youth services, where the region experiencing the greatest level, at reductions of 76%, was the North-East. The national average stands at 69%.

Those who have grown up in the poorest areas of London are much more likely to climb the social mobility ladder than their Northern counterparts. Obtaining A*-C in English and Maths at GCSE, a vital benchmark in educational attainment, is 40% more likely amongst children in London than the North. Amongst a number of social factors, this can be explained by the significant extra funding allocated to schools in London since the 1990s, something which has never been awarded for northern schools.

Is the COVID-19 outbreak improving child poverty?

Needless to say, socioeconomic status is one of the greatest risk factors in public health. Various studies have already shown that those living in deprived areas of the UK are more likely to die from the current Covid-19 outbreak.

Yet with new welfare measures brought in to avoid economic collapse, it seems some families may be better off under the current scheme.

“As we went into the present [coronavirus] crisis, child poverty rates were rising after years of austerity culminating in a freeze in out-of-work benefits,” said Professor Donald Hirsch, director of the Loughborough study. “Many families around the country are struggling to keep their heads above water, faced with uncertain income and the pressures of looking after and educating children at home. The Government’s response to [the Covid-19 outbreak] has the potential to put more money into the hands of some of those families.”

The furlough scheme and improvement of safety net incomes for families who are out of work or are in low paid jobs, hope to ease the economic uncertainties caused by the pandemic. Out-of-work families have been able to receive around £1,000 a year more under the Covid-19 scheme than if they are on Universal Credit or Working Tax Credit.

However, due to the government benefits cap, research suggests that countless households will never receive this uprating in credit. Families with children whose benefits were not capped before the outbreak (but whose new credit boost will push them up to the cap threshold), will miss out on between £185 and £412 a month. This is on top of the millions of people across the UK who still rely on the older benefits and tax credit system, including Child Tax Credit and Income Support, are not eligible for any additional financial aid during the crisis if they are not working.

Post-COVID child poverty and the North-South divide

Between 16th March and 12th May, a further 2.6 million people applied for Universal Credit on top of the estimated 2.8 million who already claim from the system. This presents a new reality for many people who have never before had to struggle in a welfare system which, at times, can seem to be working against them. Maybe it is a sign that the government has the ability to provide a better standard of welfare for those who need it under regular circumstances.

But what will happen in the aftermath of the Covid-19 crisis for child poverty? As Anna Feuchtwang, chief executive of the National Children’s Bureau and Chair for the End Child Poverty group, told the Mirror, “we may all be experiencing the storm of Coronavirus together, but we are not all in the same boat.”

Given the disparity between high-earners receiving high furlough rates and low income households being capped by the very system which hopes to better provide for them during this health crisis, it is plain to see that economic division, regardless of North-South, is engrained into British society.

The government digging into its pockets to provide for unemployed workers and low income families during this time is proof that, despite a strain on the system, there is indeed funding when it comes to the country’s welfare. As Professor David Hirsch said when asked of his study, “the logic is that if we want children to be able to live at a minimum acceptable level, these improvements, announced as temporary, should become permanent.”

Child poverty cases are set to rise by a further 1.2 million children by 2030.

Comments